TL;DR (QUICK ANSWER)

A subnet mask defines where a network ends and where individual devices begin within an IP address. It tells systems which traffic stays local, which must be routed, and how many devices a subnet can support. Understanding subnet masks and CIDR notation is essential for correct routing, better performance, stronger security, and scalable network design, while IPv6 simplifies this by using prefix length instead of traditional masks.

IP addresses tell devices where they are on a network, while subnet masks tell them which addresses are local and which are not.

Without subnet masks, every device would treat every IP as nearby. That doesn’t scale, and routing breaks almost immediately. Subnet masks exist to divide networks into smaller, manageable pieces so traffic goes where it should.

We’ll give you all the information you need about subnet masks, starting with a plain-English explanation, then moving into CIDR notation, host calculations, and practical network design decisions.

Key takeaways

- A subnet mask defines which part of an IP address is the network and which part is the host

- Subnet masks and CIDR notation represent the same network boundary in different formats

- The subnet mask determines which devices are on the same local network

- Host capacity is calculated as 2ⁿ − 2 because network and broadcast addresses are reserved

- Choosing the right subnet mask affects performance, security, and future scalability

- IPv6 uses prefix length only and does not rely on traditional subnet masks

What is a subnet mask?

A subnet mask is a 32-bit number that defines which part of an IPv4 address identifies the network and which part identifies the device.

It works alongside the IP address. The IP address identifies a device, and the subnet mask tells the device how much of that address belongs to the shared network.

For example, in this pair:

- IP address: 192.168.1.10

- Subnet mask: 255.255.255.0

The subnet mask tells the system that 192.168.1 is the network portion and .10 is the host portion. Any device with the same network portion is considered local.

Operating systems, routers, firewalls, and cloud platforms all rely on them to decide:

- Whether traffic stays local or goes to a gateway

- How routing tables are evaluated

- How broadcast traffic is handled

Without a subnet mask, an IP address doesn’t have enough context to function correctly in a network.

Tip: Need to know more information about how subnets work? Before going on, be sure to check out Subnets Explained in our Knowledge Hub.

Why subnet masks are important

Subnet masks decide how traffic moves through a network and tell devices which IP addresses are local and which ones need to be sent to a router.

They determine which devices are on the same network

When a device wants to talk to another IP address, the first question it asks is: is this destination local?

The subnet mask is how it answers that.

If the destination IP falls within the same subnet, traffic is sent directly. If not, it’s forwarded to the default gateway. Without this distinction, devices would either flood the network with unnecessary traffic, or fail to reach anything outside their immediate segment.

They control traffic and broadcast domains

Subnet masks define broadcast boundaries. Devices only receive broadcast traffic from others in the same subnet.

Smaller subnets mean smaller broadcast domains. That reduces noise and prevents one chatty segment from affecting everything else. Larger subnets increase broadcast traffic and can become inefficient as the number of devices grows.

This is one of the main reasons subnetting exists in the first place.

They improve performance and security

Splitting networks into smaller subnets limits how far traffic can spread. That has two effects:

- Less unnecessary traffic hitting every device

- Clearer boundaries for access control and filtering

Firewalls, ACLs, and routing rules often rely on subnet ranges. A clean subnet design makes it easier to isolate systems, apply policies, and troubleshoot issues when something breaks.

They enable scalable network design

Flat networks do not scale well. Subnet masks allow networks to grow in a controlled way by segmenting users, services, environments, or locations.

This applies everywhere:

- Home networks separating main and guest Wi-Fi

- Enterprise networks dividing departments or floors

- Cloud networks isolating public and private resources

Without subnetting, expansion quickly turns into rework.

What breaks if subnet masks are wrong?

- Devices think they’re on different networks and can’t talk

- Traffic is sent to the gateway unnecessarily

- Routing loops or black holes appear

- Security boundaries are accidentally bypassed

Many “mysterious” network issues trace back to a mismatched or incorrect subnet mask.

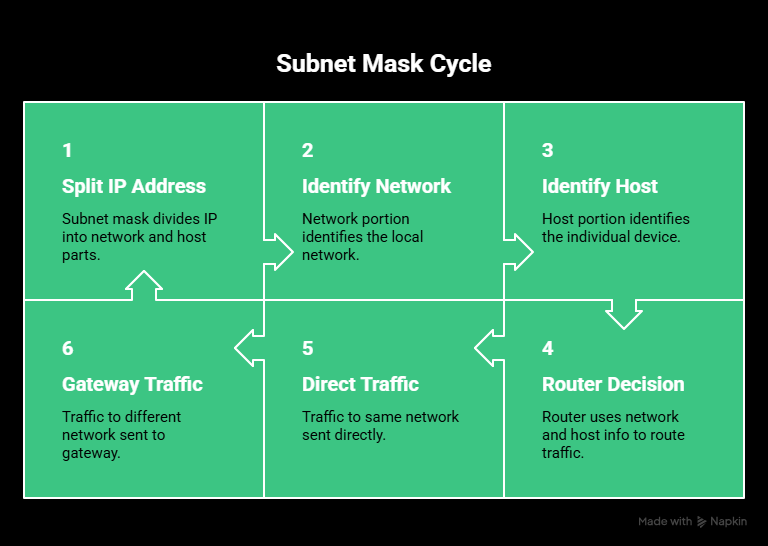

How subnet masks work (step by step)

Subnet masks work by splitting an IP address into two logical parts. One part identifies the network, and the other identifies the individual device on that network.

Everything that follows builds on that split.

Network portion vs. host portion

Every IPv4 address contains both network information and host information. The subnet mask defines where that split happens.

Take this example again:

- IP address: 192.168.1.10

- Subnet mask: 255.255.255.0

The subnet mask tells the system that the first three octets belong to the network, and the last octet belongs to the host.

So this address is interpreted as:

- Network portion: 192.168.1

- Host portion: 10

Any device whose IP address starts with 192.168.1 and uses the same subnet mask is considered part of the same local network.

This matters because routers make decisions based on that distinction. If a destination IP is on the same network, traffic is sent directly. If it’s not, traffic is sent to the default gateway.

Without a subnet mask, the router wouldn’t know where the network ends and the host begins.

Binary explanation (made simple)

Subnet masks work at the binary level. Both IP addresses and subnet masks are 32-bit values. In binary, a subnet mask is a pattern of ones followed by zeros.

- Bits set to 1 represent the network portion

- Bits set to 0 represent the host portion

When a device evaluates an IP address, it performs a logical comparison between the IP address and the subnet mask. This comparison keeps the network bits and removes the host bits.

Back to our example:

- IP address: 192.168.1.10

- Subnet mask: 255.255.255.0

In binary, this means:

- The first 24 bits are treated as the network

- The last 8 bits are treated as the host

The result of this comparison produces the network address, which identifies the subnet itself. In this case, that network address is 192.168.1.0.

Routers use this result to decide:

- Whether traffic stays on the local network

- Which routing rule applies

- Where packets should be forwarded

All of this happens automatically. Subnet masks act as filters that guide routing decisions without human input.

Common subnet mask examples

Subnet masks are usually written in dotted decimal notation, just like IP addresses.

For example:

- 255.255.255.0

- 255.255.255.192

- 255.255.255.252

Each of these values corresponds to a specific number of bits reserved for the network portion of the address. The more 255s (or high numbers) you see, the larger the network portion and the smaller the number of usable hosts.

Most commonly used subnet masks

Here are some of the subnet masks you’ll see most often in real networks:

| CIDR | Subnet mask | Total IPs | Usable hosts |

| /24 | 255.255.255.0 | 256 | 254 |

| /26 | 255.255.255.192 | 64 | 62 |

| /28 | 255.255.255.240 | 16 | 14 |

| /30 | 255.255.255.252 | 4 | 2 |

A /24 is common in home networks, small offices, and basic cloud subnets. It provides enough space for most environments without overthinking IP allocation.

A /26 is often used when you need tighter control. It’s large enough for a small team or service group, but small enough to reduce broadcast traffic and limit exposure.

A /28 works well for small segments like management networks, test environments, or isolated services that only need a handful of addresses.

Finally, a /30 is usually reserved for point-to-point links, such as router-to-router connections, where only two usable IPs are needed.

Choosing the right subnet size is a balance between capacity and efficiency. Oversized subnets waste addresses, but undersized ones force redesign later.

Tip: Need help remembering subnets? Use our Subnet Cheat Sheet & Guide to take the guesswork out.

CIDR notation and how it relates to subnet masks

CIDR notation is a shorter way to represent a subnet mask. Instead of writing out the full dotted decimal mask, CIDR uses a number after a slash to show how many bits belong to the network.

Another example:

- 192.168.1.0/24

- 10.0.0.0/16

The number after the slash tells you how many bits are reserved for the network portion of the address.

So when you see /24, it means the first 24 bits are the network, and the remaining 8 bits are used for hosts.

CIDR exists because older, class-based networking was too rigid. Networks were locked into fixed sizes that wasted large numbers of IP addresses. CIDR removed those limits and allowed networks to be sized more precisely based on actual need.

Today, CIDR notation is the standard format used in:

- Routing tables

- Firewall rules

- Cloud networking platforms

- IP allowlists and blocklists

Subnet masks and CIDR describe the same boundary, they just do it in different formats.

How to convert CIDR to a subnet mask

To convert CIDR notation to a subnet mask, you translate the number of network bits into dotted decimal form. Start with the CIDR value. Let’s take /26.

A /26 means:

- 26 bits set to 1 for the network

- 6 bits set to 0 for hosts

Written in binary, that looks like this:

11111111.11111111.11111111.11000000

Now convert each group of eight bits into decimal:

- 11111111 = 255

- 11111111 = 255

- 11111111 = 255

- 11000000 = 192

The resulting subnet mask is 255.255.255.192.

That’s all the conversion is doing. It’s turning a count of network bits into a readable mask. Once you understand that, CIDR notation stops being abstract. It’s just a compact way of expressing where the network ends and the host range begins.

How many hosts can a subnet support?

The number of devices a subnet can support depends on how many bits are left for the host portion of the IP address. The subnet mask defines that split.

In IPv4, the calculation follows a simple rule:

2ⁿ − 2, where n is the number of host bits.

The subtraction of two accounts for addresses that cannot be assigned to devices. One address identifies the network itself, and one address is reserved for broadcast traffic.

Why network and broadcast addresses are reserved

Every subnet has two special addresses:

- The network address, where all host bits are set to 0

- The broadcast address, where all host bits are set to 1

These addresses are used by the network and cannot be assigned to individual devices. That’s why usable hosts are always fewer than total IPs.

Practical examples

A /24 subnet leaves 8 bits for hosts.

- 2⁸ = 256 total IP addresses

- 256 − 2 = 254 usable hosts

This is why a /24 never gives you 256 usable devices, even though the math looks close.

A /26 subnet leaves 6 bits for hosts.

- 2⁶ = 64 total IPs

- 64 − 2 = 62 usable hosts

This size is common when you want tighter control without redesigning your network later.

A /30 subnet leaves only 2 bits for hosts.

- 2² = 4 total IPs

- 4 − 2 = 2 usable hosts

That’s why /30 subnets are often used for point-to-point links between routers.

Tip: More host bits = more devices, fewer subnets. Fewer host bits = fewer devices, more subnets.

How to choose the right subnet mask

Choosing a subnet mask is a planning decision, not a default setting. The objective is to give each network segment enough IPs to function comfortably without wasting address space or creating unnecessary broadcast traffic.

A good subnet mask fits how the network is used today and how it’s likely to grow.

Start with how many devices you actually need

Count everything that requires an IP address:

- User devices

- Servers and VMs

- Printers, cameras, IoT devices

- Load balancers, gateways, and management interfaces

Plan for growth, not just today

Subnetting is easier to do once than to redo under pressure. If you expect headcount, services, or automation to expand, choose a subnet that gives you breathing room.

It’s usually better to slightly oversize a subnet than to hit capacity and be forced to renumber devices later.

In cloud environments, this matters even more. Running out of IPs in a subnet can block scaling operations and require disruptive changes.

Segment by function or trust level

Subnet masks are used to create boundaries between different parts of a network.

Common segmentation patterns include:

- Separating users from servers

- Isolating production, staging, and development

- Placing guest or IoT devices in restricted subnets

Each segment gets its own subnet sized to its purpose. Smaller, focused subnets are easier to secure and troubleshoot than one large flat network.

Consider performance and broadcast traffic

Larger subnets mean more devices sharing the same broadcast domain. That can become noisy as the number of hosts grows.

If a subnet contains hundreds of devices that frequently broadcast, splitting it into smaller subnets can improve performance and stability. This is particularly relevant in enterprise LANs and device-heavy environments.

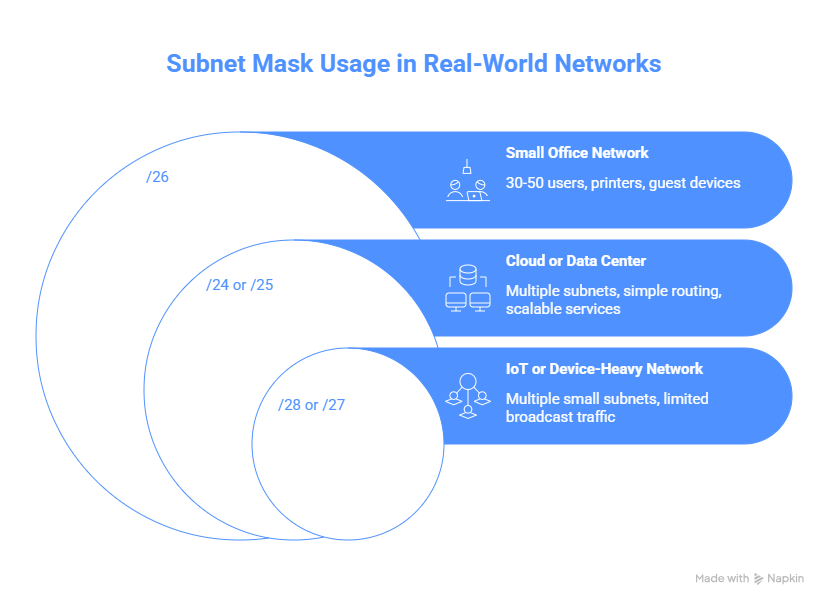

Real-world examples

To help you understand how this information can be applied in real life, we’ve put together a few examples:

Small office network

An office with 30-50 users typically fits well in a /26. It supports current needs while leaving room for printers, guest devices, and future hires.

Cloud or data center environment

Cloud networks often use multiple /24 or /25 subnets spread across availability zones. You’ll keep routing simple while allowing services to scale independently.

IoT or device-heavy network

Environments with many small devices often use multiple small subnets, such as /28 or /27, to limit broadcast traffic and isolate failures.

The right subnet mask depends on usage patterns, growth expectations, and operational complexity. There is no single “correct” size, only a size that fits the job.

Subnet masks in real-world networking

Subnet masks show up everywhere, even when you’re not actively thinking about networking. The concepts stay the same, but how they’re applied depends on the environment.

Home networks

Most home routers use a /24 subnet by default, usually something like 192.168.0.0/24 or 192.168.1.0/24. That gives up to 254 usable IP addresses, which is more than enough for phones, laptops, TVs, and smart devices.

In simple setups, everything lives on one subnet. In more advanced home networks, you might see additional subnets for:

- Guest Wi-Fi

- IoT devices

- Home lab or test systems

The subnet mask controls which devices can talk directly and which must go through the router or firewall rules.

Enterprise networks

In enterprise environments, subnet masks are used to divide networks by department, floor, or function.

For instance:

- HR: 10.20.1.0/24

- Engineering: 10.20.2.0/24

- Finance: 10.20.3.0/24

Each subnet has a defined boundary. Traffic crossing that boundary can be filtered, logged, or blocked, which keeps broadcast traffic contained and simplifies access control.

Smaller subnets are often paired with VLANs so logical separation exists even when devices share the same physical infrastructure.

VLANs and segmentation

VLANs operate at Layer 2, while subnet masks define IP boundaries at Layer 3. Most network designs assign a single subnet to each VLAN.

For example:

- VLAN 10 → 192.168.10.0/24

- VLAN 20 → 192.168.20.0/24

A one-to-one mapping makes routing predictable and minimizes confusion during troubleshooting.

Cloud networking

Cloud platforms require subnetting from the start. You can’t launch resources without defining CIDR blocks.

A common cloud setup might look like:

- VPC: 10.0.0.0/16

- Public subnet: 10.0.1.0/24

- Private subnet: 10.0.2.0/24

Subnet masks define how traffic flows between services, load balancers, gateways, and the internet. They also determine how many resources a subnet can support.

Poor subnet planning in the cloud often shows up later as scaling limits or routing conflicts. Choosing sensible subnet sizes early avoids painful changes down the line.

IPv4 vs. IPv6 subnetting

Subnetting exists in both IPv4 and IPv6, but it works very differently in practice. Understanding that difference helps avoid a lot of confusion, especially when working with modern networks or monitoring mixed environments.

Tip: What’s the difference? Find out more in our guide to IPv4 and IPv6 to learn everything you need to know.

IPv4 subnetting

IPv4 uses 32-bit addresses. Subnetting in IPv4 is largely about conserving address space and fitting networks to specific sizes.

That’s why IPv4 subnetting focuses on:

- Calculating usable hosts

- Choosing the smallest possible subnet

- Avoiding wasted IPs

- Working around address exhaustion

Subnet masks like 255.255.255.0 or CIDR values like /26 exist to finely control how many devices a subnet can support. In IPv4, subnetting is a balancing act.

IPv6 subnetting

IPv6 uses 128-bit addresses. Address exhaustion is not the problem it’s solving. Because of that, IPv6 does not use traditional subnet masks. Instead, it relies entirely on prefix length.

You’ll typically see IPv6 subnets written like this:

2001:db8:abcd:0012::/64

The /64 means the first 64 bits identify the network. The remaining 64 bits identify the host.

This is not a recommendation, it’s a convention. In IPv6, almost every subnet is a /64.

Why IPv6 subnetting is simpler

IPv6 subnetting is simpler because it prioritizes structure over efficiency.

- No need to calculate usable hosts

- No need to subtract network or broadcast addresses

- No pressure to tightly size subnets

A single /64 subnet supports an enormous number of devices. That lets engineers focus on logical segmentation instead of address math.

Subnetting in IPv6 is mainly about:

- Organizing networks

- Separating environments

- Defining routing boundaries

Not squeezing addresses to fit.

Key differences at a glance

| Aspect | IPv4 | IPv6 |

| Addressing method | Uses subnet masks and CIDR to manage address scarcity | Uses prefix length to define network structure |

| Host calculations | Requires careful host and subnet size calculations | Largely removes host-count concerns |

If you treat IPv6 like “bigger IPv4,” things stop making sense quickly. The design goals are different, and the subnetting model reflects that.

Common subnet mask mistakes and troubleshooting

Subnet mask issues tend to look like routing problems, DNS failures, or firewall bugs. In reality, the mask is often the root cause. These are the mistakes that show up most often in real environments.

Overlapping subnets

Overlapping subnets confuse routers. If two interfaces or networks use IP ranges that overlap, routing decisions become unpredictable.

Example:

- VLAN 10: 10.0.0.0/24

- VLAN 20: 10.0.0.0/16

Traffic meant for the smaller subnet may get routed into the larger one. Depending on route priority, packets may disappear or loop.

Fix: Make sure every subnet is unique and clearly scoped. Avoid mixing large and small prefixes in the same address space unless route design is intentional.

Mismatched subnet masks on devices

If two devices are on the same IP range but use different subnet masks, they may disagree about what’s local.

Example:

- Device A: 192.168.10.5/24

- Device B: 192.168.10.6/16

Device A sees Device B as local. Device B sees Device A as remote and sends traffic to the gateway. Communication breaks in one direction.

Fix: Verify that devices in the same subnet use the same mask, especially when mixing DHCP and static IPs.

Wrong subnet mask on the default gateway

The gateway must use the same subnet definition as the devices it serves. If the gateway mask is wrong, traffic may never leave or return correctly. This is common after manual changes or partial migrations.

Fix: Check the gateway IP and subnet mask together. They should describe the same network as the connected hosts.

Miscalculated host ranges

Assigning IPs outside the valid host range causes silent failures.

Example:

- Subnet: 192.168.1.0/24

- Network address: 192.168.1.0

- Broadcast address: 192.168.1.255

Neither of those can be assigned to a device. Doing so may appear to work intermittently, then fail in confusing ways.

Fix: Confirm usable ranges before assigning static IPs.

Cloud networking pitfalls

Cloud platforms enforce subnet boundaries strictly. If a subnet is too small, scaling fails. If CIDR blocks overlap between VPCs or VNets, peering breaks.

Fix: Plan CIDR ranges early. Leave space between blocks. Avoid tight subnetting unless you are certain about growth limits.

Quick troubleshooting checklist

When subnet-related issues appear, check these basics first:

- Confirm IP address and subnet mask on the device

- Verify default gateway IP and mask

- Check for overlapping routes

- Confirm DHCP scopes match subnet definitions

- Test local vs routed traffic paths

Subnet mask problems often hide behind symptoms elsewhere. Before digging into DNS, firewalls, or application logs, confirm the address math.

Subnet mask tools and calculators

Subnet calculators help you work faster and avoid mistakes, especially once networks grow beyond simple /24 setups. Instead of doing binary math by hand, you enter an IP address and prefix, and the tool returns the network address, usable range, broadcast address, and host count.

They’re not a substitute for understanding subnetting, but they remove unnecessary frustration once you know what you’re checking.

For command-line workflows, tools like ipcalc are common. They let you calculate subnet details directly in the terminal, which is useful when working on servers, network devices, or cloud instances where a browser isn’t available.

Manual calculation still matters when you’re learning subnetting or debugging edge cases. Knowing how the numbers are derived helps you spot bad assumptions, overlapping ranges, or incorrect masks. In day-to-day work, though, calculators are faster and more reliable.

If you want a quick, browser-based option, UptimeRobot’s free subnet calculators can help you validate ranges and host counts without switching tools. We have both an IPv6 subnet calculator, and an IPv4 version.

Subnet mask vs. related concepts

Subnet masks often get mixed up with other networking terms. They’re related, but they’re not interchangeable. Clearing this up makes configuration and troubleshooting much easier.

Subnet mask vs. CIDR notation

These describe the same thing in different formats.

- Subnet mask: 255.255.255.0

- CIDR notation: /24

Both indicate how many bits belong to the network portion of the IP address. CIDR is shorter, easier to read, and more common in modern tooling. Subnet masks still appear in operating systems, legacy configs, and documentation.

Subnet mask vs. default gateway

The subnet mask defines what is local, and the default gateway defines where traffic goes when it is not local.

If an IP address falls within the local subnet (as defined by the mask), traffic is sent directly. If it falls outside, traffic is sent to the gateway.

You need both for a device to communicate reliably beyond its own subnet.

Subnet mask vs. VLAN

A subnet mask defines an IP boundary. A VLAN defines a Layer 2 broadcast domain. They are often used together, but they solve different problems:

- VLANs separate traffic at the switch level

- Subnets separate traffic at the IP and routing level

You can have multiple VLANs with the same subnet (not recommended) or one VLAN with multiple subnets (common in routing-heavy designs). Clean designs usually map one VLAN to one subnet for clarity.

Conclusion

Subnet masks define where a network starts and ends. They tell devices which IPs are local, when traffic needs to be routed, and how many hosts a subnet can support.

Once you understand how the network and host portions are separated, the rest stops feeling abstract. CIDR makes sense, host counts follow predictable rules, and most troubleshooting begins with the subnet mask and gateway.

Problems typically arise when subnet masks are mis-sized or not applied consistently. Choosing straightforward masks and documenting them with future growth in mind avoids many common failures.

FAQ's

-

/24 means that the first 24 bits of the IP address are used for the network portion.

It corresponds to the subnet mask 255.255.255.0 and provides 256 total IP addresses, with 254 usable for devices. -

Yes. A subnet mask must have contiguous 1s followed by contiguous 0s in binary. Masks like 255.255.0.255 are invalid and will cause routing and communication issues.

-

Because two addresses are reserved:

- One for the network address (all host bits set to 0)

- One for the broadcast address (all host bits set to 1)

That leaves 254 usable addresses for hosts.

-

No. IPv6 does not use traditional subnet masks. It uses prefix length only (for example, /64). IPv6 subnetting is simpler conceptually because address exhaustion is not a concern and subnet sizes are standardized.

-

Devices may think they are on different networks even if their IPs look similar. This can cause traffic to be sent to the gateway incorrectly or dropped entirely. Mismatched masks are a common cause of “it should work, but it doesn’t” network issues.