Severity levels help teams assess incident impact quickly and respond in a consistent way. When they’re well-defined, they remove guesswork during outages, align technical and business teams, and prevent overreaction to minor issues.

In reality, many teams struggle with severity. Definitions are vague, applied inconsistently, or confused with priority and urgency. The result is alert fatigue, slow escalation for real incidents, and burned-out on-call engineers.

This guide explains how severity levels work from top to bottom.

Key takeaways

- What severity levels are and how they differ from priority and urgency

- What SEV1-SEV5 typically represent, with clear examples

- How to assign severity based on impact, scope, and risk

- How severity levels affect response time, escalation, and communication

- Common mistakes teams make and how to avoid them

What are severity levels?

Severity levels are predefined categories that describe the impact of an incident, not how hard it is to fix. They’re used across engineering, support, and operations teams to align response efforts and expectations.

While exact definitions vary between companies, most teams follow a similar structure. The same technical issue can fall under different severity levels depending on who is affected and how critical the impact is.

For instance, a reporting dashboard failing overnight might be low severity if it affects only internal teams. The same failure during business hours that blocks customer access could be high severity.

Why severity levels matter in incident management

Severity levels give teams a shared reference point during incidents. Without them, response depends too much on who’s on call, how loud the alert is, or how stressful the moment feels.

Clear severity definitions reduce inconsistency and help teams focus on impact instead of panic.

Faster decisions during incidents

Incidents rarely come with full context upfront. Severity levels help teams make an initial call without debating every detail.

They reduce hesitation at the start of an incident and limit two common problems:

- Pulling too many people into low-impact issues

- Treating serious outages as routine bugs

That keeps attention where it belongs and limits alert fatigue over time.

Fewer explanations between teams

Severity labels shorten conversations. When support, engineering, or leadership see a severity level, they immediately understand the expected scope and urgency.

That matters most during live incidents, when time is limited and updates need to stay short. It also helps when teams are distributed or on-call rotations change frequently.

More predictable escalation

Severity levels usually map to response expectations. Higher severity means faster response and broader coordination. Lower severity allows for asynchronous handling without disrupting unrelated work.

With this mapping in place, teams don’t have to decide escalation rules from scratch every time something breaks.

Clearer patterns after incidents

Looking at incidents by severity makes patterns easier to spot. Repeated high-severity incidents often point to weak dependencies or missing safeguards. Recurring lower-severity issues can highlight usability or reliability gaps that still affect customers over time.

Severity data helps teams prioritize fixes based on impact, not just volume.

Severity vs. priority vs. urgency (commonly confused)

Severity, priority, and urgency are not the same thing. Mixing them up leads to bad triage decisions and inconsistent incident response.

Let’s specify each:

Severity: how bad is the impact?

Severity measures the scope of impact. It answers one question: how bad is this for users or the business?

It doesn’t consider how fast the issue can be fixed or how many people are available to work on it. A full production outage affecting all users is high severity, and a broken UI element in an internal admin tool is low severity.

Severity is usually assessed first, based on impact alone.

| Incident | Severity |

| Entire website down with no fallback | SEV1 |

| Payment gateway timing out for 10% of users | SEV2 |

| Broken image on homepage | SEV4 |

Urgency: how fast action is needed

Urgency reflects time sensitivity. It asks how quickly action is required to prevent further impact.

An issue can be low severity but high urgency. A certificate about to expire is a common example. Nothing is broken yet, but delay guarantees a future outage.

Urgency can change over time. If an issue is ignored, urgency often grows in intensity.

Examples:

- SSL certificate expiring in 24 hours: low severity, high urgency

- Bug in a deprecated feature: low urgency

- Message queue growing steadily: urgency increases as backlog grows

Priority: what gets worked on first

Priority determines execution order. It combines severity and urgency with real-world constraints.

Two incidents with the same severity may not have the same priority.

As an example, a SEV2 affecting a major customer during a launch may outrank a SEV2 in a test environment, and a SEV1 at 3 a.m. may wait if the on-call team is already handling another critical incident.

Priority reflects judgment in the moment, not classification.

It’s shaped by:

- SLAs (Service Level Agreements)

- Customer impact

- Team capacity

- Business context

| Severity | Urgency | Example | Priority |

| High | High | Site outage during sale | P1 |

| High | Low | Broken reporting tool | P2 |

| Low | High | SSL certificate expiring | P2 |

| Low | Low | Minor UI glitch | P4 |

Why the distinction matters

When these terms are blurred, triage breaks down. Low-severity but high-urgency issues get ignored. High-severity but low-urgency issues pull in too many people too fast.

Clear separation lets teams:

- Triage alerts consistently

- Communicate impact without long explanations

- Align response with real business risk

Common severity level models (SEV1-SEV5)

Most organizations use a tiered model, typically SEV1 through SEV5, to classify incidents and determine response urgency. These levels guide how fast teams respond, who gets involved, and how communication flows internally and externally.

Let’s break down what each severity level typically means in a standard SEV1–SEV5 model.

SEV1: Critical

SEV1 covers incidents that stop the system from functioning. Core services are unavailable, users are blocked, or data is at risk. There is no meaningful workaround.

These incidents take priority over everything else until resolved.

SEV2: High

SEV2 issues cause major disruption without a full outage. A key feature may be broken, or a large group of users may be affected. Workarounds, if they exist, are limited.

The issue needs fast attention, but the impact is more contained than SEV1.

SEV3: Medium

SEV3 includes problems that affect functionality without blocking core use. Performance may be degraded, or non-critical features may misbehave.

Users can usually continue working, though the experience is worse than expected.

SEV4: Low

SEV4 issues have little practical impact. These are often cosmetic bugs, edge cases, or problems affecting a small number of users.

They’re logged and handled alongside other planned work.

SEV5: Informational (optional)

Some teams use SEV5 for events that don’t require action. These are tracked for visibility or trend analysis rather than response.

SEV5 does not trigger escalation.

Here’s a quick example table of all 5 levels to give you a clearer picture:

| Severity level | Impact | Users affected | Example |

| SEV1 | Complete outage or data loss | Most or all users | Production API unavailable |

| SEV2 | Major functionality degraded | Large subset of users | Checkout failing in one region |

| SEV3 | Partial disruption | Some users | Reports loading slowly |

| SEV4 | Minor issue | Few or no users | UI alignment bug |

| SEV5 | No immediate impact | No users | Certificate nearing expiry |

Severity level examples by industry

What counts as a SEV1 in one industry might be a SEV3 somewhere else. Context matters. Below is how severity levels typically play out across IT ops, security, and SaaS support teams.

IT operations and infrastructure

In IT ops, severity levels are often tied to service availability, performance degradation, or infrastructure failures. These teams rely on clear definitions so they can respond fast and avoid downstream impact.

Examples:

- Severity 1: A core production database is unreachable, affecting all customer transactions. No workaround exists. Revenue is at risk.

- Severity 2: A load balancer fails over to a backup, causing intermittent latency for 30% of users. Services are degraded but partially functional.

- Severity 3: A monitoring agent on a staging server stops reporting. No customer impact, but needs attention during business hours.

- Severity 4: A non-critical backup job fails. Logged for review, no immediate action required.

These levels often map to SLAs and on-call escalation policies. For example, a SEV1 might trigger a 15-minute response window and require immediate coordination across teams.

Security and SOC teams

Security teams use severity levels to triage alerts and incidents based on threat level, exposure, and potential damage. A failed login attempt isn’t the same as a confirmed data exfiltration.

Examples:

- Severity 1: Active ransomware detected on production servers. Lateral movement confirmed. Immediate containment and incident response initiated.

- Severity 2: A phishing email successfully compromises a user account with access to sensitive internal systems. Limited exposure, but high risk.

- Severity 3: Multiple failed login attempts from a foreign IP. No successful breach, but worth monitoring.

- Severity 4: Outdated software version flagged in a low-risk internal tool. Logged for patching in the next sprint.

Unlike IT ops, security incidents can escalate quickly. A SEV3 alert might become a SEV1 if new evidence surfaces. SOC teams often use automation to reclassify alerts based on threat intelligence or behavioral analytics.

SaaS product and customer support

For SaaS companies, severity levels are often customer-facing. They influence how support tickets are triaged, how engineering gets looped in, and how status pages are updated.

Examples:

- Severity 1: Login failures across all regions. All users are blocked from accessing the product. Public status page updated, engineering on-call paged.

- Severity 2: A major feature (like billing or reporting) is down for a subset of users. Support team fields complaints, workaround available.

- Severity 3: A UI bug affects layout in Safari browsers. Functionality is intact, but user experience is degraded.

- Severity 4: A customer requests a feature enhancement or reports a minor typo. No action needed beyond acknowledgment.

Severity levels here aren’t just internal, they shape customer communication. A SEV1 might trigger proactive outreach, while a SEV4 gets added to the product backlog.

Severity level definitions should reflect your industry’s risk tolerance, customer expectations, and operational model. Keep in mind that your definitions might look different than what we’ve described here.

How to assign severity levels correctly

Overestimating severity levels can trigger unnecessary alerts and burn out your team. The goal is consistency: every incident should be evaluated using the same criteria, regardless of who’s on call.

Consistency requires clear criteria based on measurable impact.

Core factors to evaluate

These are the four core dimensions to consider:

- User impact: How many users are affected? Are they blocked from using the product, or is it a minor degradation? A full outage for all users is a higher severity than a bug affecting a single browser version.

- Business impact: Does the issue affect revenue, transactions, or key conversion flows? For example, a checkout failure on an e-commerce site is more severe than a broken image on a blog.

- Duration and scope: Is this a one-off event, or is it ongoing? A transient spike in latency might not justify a high severity, but a persistent slowdown over 30 minutes likely does.

- Workarounds: Can users still complete their tasks another way? If there’s no workaround, the severity goes up. If support can guide users through a temporary fix, that might lower it.

Each of these factors should be documented in your incident response playbook. That way, responders don’t have to guess, they can reference shared definitions.

Here’s a quick example:

| Incident | User Impact | Business Impact | Workaround | Suggested Severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Login API down | All users can’t log in | Blocks access to product | None | High |

| Analytics delay | Admins see outdated data | No direct revenue impact | Wait 10 mins | Low |

| Payment gateway timeout | 20% of payments fail | Revenue loss | Retry works | Medium |

A simple severity scoring approach

User impact:

0 = No users affected

1 = Few users affected

2 = Many users affected

3 = All users affected

Business impact:

0 = No measurable impact

1 = Minor inconvenience

2 = Revenue-affecting

3 = Business-critical

Workaround availability:

0 = Easy workaround

1 = Temporary workaround

2 = Hard workaround

3 = No workaround

Duration:

0 = Resolved in under 5 minutes

1 = 5-30 minutes

2 = 30-60 minutes

3 = Ongoing for more than an hour

The total score provides a starting point:

0-3: Low

4-6: Medium

7-9: High

10-12: Critical

Scoring won’t be perfect, but it helps teams avoid gut-feel decisions under pressure. It works best when reviewed after incidents. If the score didn’t match the real impact, the criteria should be adjusted.

Getting the initial severity right sets expectations for everything that follows, from escalation to communication to post-incident review.

Incident severity matrix (practical framework)

A severity matrix is used to assign severity consistently during triage. It maps observable impact to a predefined severity level so teams can respond without debating classification during an incident.

Most teams use a 4 or 5 level model, and severity is typically evaluated across a small set of dimensions:

- Customer impact: How many users are affected, and whether core actions are blocked

- Functionality loss: Whether a critical feature is unavailable or degraded

- Business impact: Revenue loss, SLA risk, or blocked workflows

- Time sensitivity: Whether delay increases impact

Here’s an example of a four-level incident severity matrix:

| Severity | Description | Example | Response Expectation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEV1 | Major outage or data loss affecting most users or core functionality | API is down globally, customers can’t log in | Immediate response, 24/7 on-call, exec-level comms |

| SEV2 | Partial outage or degraded performance for a large user group | Dashboard loads slowly for EU users | Respond within 30 minutes, comms to affected users |

| SEV3 | Minor issue with limited impact or workaround available | Email notifications delayed, but retry works | Triage during business hours, update status page if needed |

| SEV4 | Cosmetic or non-urgent bug, no user impact | UI misalignment in Firefox | Add to backlog, no immediate action |

This matrix should be documented and easy to find. It should also be reviewed quarterly with input from engineering, support, and product teams. If you’re using public status pages, align your severity levels with the incident types shown there.

How severity levels drive SLAs and escalation

Severity levels are used to set response expectations. Each level maps to defined response and resolution targets so teams know when to act and when to escalate.

Response and resolution timeframes

Teams typically define these targets ahead of time so response expectations are clear during incidents.

For instance:

| Severity | Description | Response Time | Resolution Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| SEV1 | Complete outage or critical business impact | 15 minutes | 2 hours |

| SEV2 | Degraded performance or partial outage | 30 minutes | 4 hours |

| SEV3 | Minor issue or workaround available | 1 hour | 1 business day |

| SEV4 | Informational or cosmetic | 4 hours | 3 business days |

Escalation paths depend on severity

Escalation paths are usually tied directly to severity:

- SEV1: Immediate paging of on-call engineer, auto-escalation to engineering manager if not acknowledged in 10 minutes, incident commander assigned, cross-functional war room initiated.

- SEV2: On-call engineer paged, escalation to team lead if unresolved in 30 minutes, Slack channel created for coordination.

- SEV3: Logged as a ticket, triaged during business hours, no paging unless it escalates.

- SEV4: Added to backlog, reviewed in weekly triage.

Escalation rules should be codified in tooling rather than handled manually. This reduces reliance on tribal knowledge and keeps responses predictable.

Severity levels shape stakeholder communication

Severity also determines how incidents are communicated:

- A SEV1 incident might trigger a status page update, customer email, and executive alert within 30 minutes.

- A SEV2 might require only internal updates and a post-mortem if SLAs are breached.

- SEV3 and SEV4 issues may not require real-time updates but should still be tracked and communicated during retros or sprint reviews.

Without clear links between severity and communication, teams risk over-communicating minor issues or under-communicating major ones.

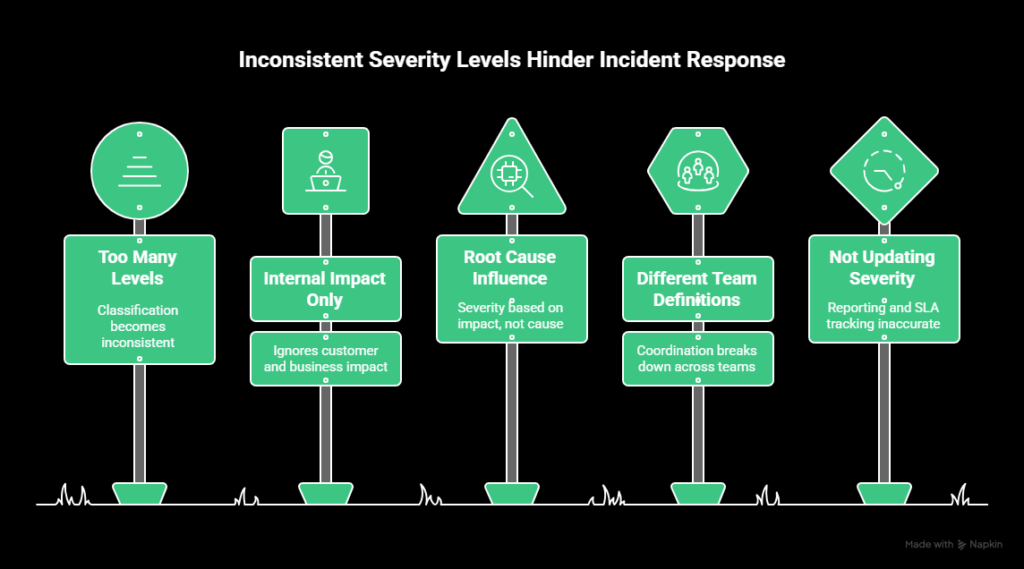

Common mistakes when defining severity levels

Severity models fail most often because they’re applied inconsistently. The definitions exist, but teams interpret them differently under pressure. That leads to slow triage, unnecessary escalation, or missed incidents.

These are the most common issues.

Using too many severity levels

Adding more levels doesn’t make classification more accurate. It usually does the opposite. When the difference between two levels isn’t obvious, teams spend time debating severity instead of responding.

In most cases, teams do well with three or four levels. Beyond that, classification becomes inconsistent and subjective.

Defining severity based on internal impact only

Severity should reflect customer and business impact first. Internal convenience is not a reliable signal.

If a public API is unavailable but internal dashboards still work, the incident is still high severity. Customers are blocked, regardless of how internal systems look.

Always assess impact from the user’s perspective.

Letting root cause influence severity

Severity is based on impact, not on why the issue happened.

A known bug causing login failures for a portion of users doesn’t become lower severity because it’s familiar. If the impact is significant, the severity should reflect that.

Root cause matters for diagnosis and prevention, not for classification.

Using different definitions across teams

Severity only works if everyone uses the same definitions. If support, engineering, and product teams interpret severity differently, coordination breaks down.

Severity levels should be documented with clear definitions and examples. These should be reviewed regularly to keep teams aligned.

Not updating severity as impact becomes clear

Initial severity is often assigned with limited information. As incidents unfold, impact may increase or decrease.

If severity is not updated, reporting and SLA tracking become inaccurate. Teams should reassess severity once scope and impact are confirmed and adjust it when needed.

Best practices for defining and using severity levels

Severity levels only work if they’re simple, documented, and applied the same way every time. These practices help keep classification consistent as teams and systems scale.

Use a single, documented severity scale

Define one severity scale and use it everywhere. The exact number of levels matters less than consistency.

Each level should be defined in terms of:

- User impact

- Business impact

- Scope

- Workaround availability

Avoid adding dimensions that don’t affect impact. If a factor doesn’t change severity, it doesn’t belong in the definition.

Tie severity to impact, not metrics alone

System metrics don’t tell the full story. The same error rate can have very different consequences depending on where it occurs.

Severity should reflect user experience and business risk, not just CPU usage, latency, or error percentages.

Make severity assignment fast

Severity should be assigned quickly during triage. Teams should not debate classification for long periods while impact is unfolding.

Severity matrices, short descriptions, and predefined criteria help responders make consistent calls under pressure.

Reassess severity as incidents evolve

Initial severity is often based on partial information. As scope and impact become clearer, severity should be updated.

Keeping severity accurate matters for reporting, SLA tracking, and post-incident analysis.

Use severity to drive response and communication

Each severity level should map to clear expectations for response, escalation, and communication. If severity does not change behavior, it is not doing its job.

Severity definitions should align with status pages, alerting rules, and escalation policies so users and internal teams see consistent signals.

Conclusion

Clear severity definitions make incident response easier to manage and scale. When severity is based on impact and applied consistently, teams spend less time debating classifications and more time resolving real issues.

If you’re looking to apply severity levels in practice, UptimeRobot can help. You can monitor availability, performance, certificates, and key endpoints, then route alerts based on what actually matters.

You can create a free UptimeRobot account and get 50 monitors to start tracking critical services and setting up alerting that fits your incident workflow.

FAQ's

-

SEV1 indicates a complete outage or failure of a core service that blocks users or causes direct business impact. There is usually no workaround. SEV2 covers major disruption where the system is still partially functional or the impact is limited to a subset of users. The key difference is scope and tolerance for delay, not effort to fix.

-

Most teams work best with 3-5 levels. Fewer levels make classification easier and more consistent. Too many levels tend to create confusion and slow triage. What matters more than the number is having clear definitions that everyone uses the same way.

-

Initial severity is usually set by the on-call engineer or first responder during triage. In larger incidents, that decision may be confirmed or adjusted by an incident lead. Severity should follow documented criteria, not personal judgment or seniority.

-

Yes. Severity is often assigned with limited information and should be updated as impact becomes clearer. If an issue spreads, blocks more users, or affects critical systems, severity should be raised. If impact turns out to be smaller than expected, it can be lowered. Accuracy matters more than sticking with the first call.

-

No. The structure is similar, but how severity is applied depends on context. A short outage might be SEV1 for a payments platform and SEV2 for an internal tool. Industry, customer expectations, and business risk all influence how severity levels are defined and used.