TL;DR (QUICK ANSWER)

Cardinality in databases has two meanings:

• Column cardinality, the number of distinct values in a column, which affects indexing, filtering, and query performance.

• Relationship cardinality, how tables connect, such as one to one or one to many, which shapes schema design and joins.

Databases rely on cardinality estimates to choose execution plans. High cardinality often improves index effectiveness, while incorrect estimates can slow queries. Understanding both types helps you design faster, cleaner, and more scalable databases.

Cardinality is a foundational concept in database design and performance. It influences how tables relate to each other, which columns should be indexed, and how the query optimizer builds execution plans.

In databases, cardinality appears in two main ways:

- Column cardinality, which describes how many distinct values exist in a column

- Relationship cardinality, which defines how records in one table connect to records in another

Both matter. Column cardinality affects filtering efficiency and index usefulness, and relationship cardinality shapes schema structure and join behavior. Together, they determine how efficiently your database stores and retrieves data.

Many guides oversimplify cardinality as just “uniqueness.” This article covers both meanings in depth and explains how they impact indexing, selectivity, and cardinality estimation in real SQL systems.

Key takeaways

- Cardinality has two meanings in databases: column and relationship.

- Column cardinality affects indexing and filtering performance.

- Relationship cardinality affects schema design and joins.

- Cardinality estimation drives query optimizer decisions.

- Understanding both prevents performance and modeling mistakes.

What is cardinality in a database?

Cardinality refers to how unique data is within a dataset. In databases, it describes either the distinctness of values in a column or the structure of relationships between tables.

Because databases rely on this information to build indexes and execution plans, cardinality directly affects performance and data modeling.

In practice, these two uses of cardinality show up differently.

Column or data cardinality

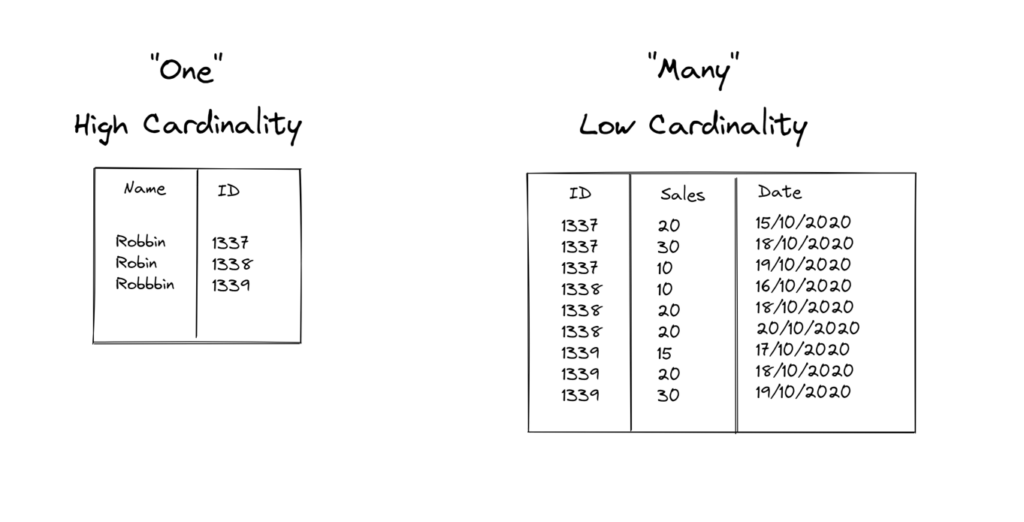

Column cardinality describes how many unique values exist in a specific column. For example, a user ID column typically has very high cardinality because each row has a different value. On the other hand, a status column with values like “active,” “paused,” or “disabled” has low cardinality because the same values repeat across many rows.

This matters because databases use column cardinality to make decisions about indexing and query plans.

High cardinality columns are often good candidates for indexes. Low cardinality columns usually are not, unless they are combined with other fields or used in very specific query patterns.

Relationship cardinality

Relationship cardinality describes how tables relate to each other. It answers questions like how many rows in one table can be connected to rows in another table. Common examples include one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many relationships.

For instance, one user can have many uptime monitors, which makes it a one-to-many relationship. In contrast, a monitor might belong to multiple alerting rules, which creates a many-to-many relationship.

Understanding relationship cardinality helps you choose the right table structure, define foreign keys correctly, and avoid data duplication or integrity issues.

Both types of cardinality work together. Column cardinality influences performance, while relationship cardinality shapes how your data is organized. Knowing the difference makes it much easier to design databases that are both clean and fast.

Column cardinality explained (data cardinality)

Column cardinality, also called data cardinality, focuses on the values inside a single column. It is one of the first things a database looks at when deciding how to store data and how to run queries efficiently.

What is column cardinality?

Column cardinality refers to the number of distinct values in a column compared to the total number of rows in the table.

If a table has 1,000,000 rows and 1,000,000 unique values in a column, that column has very high cardinality. If the same table has only five unique values in a column, that column has low cardinality.

Databases use this information heavily during indexing and query planning. When you run a query, the database estimates how many rows it will need to scan. Column cardinality helps it decide whether an index will be useful or if a full table scan makes more sense.

You can measure column cardinality directly with a simple SQL query:

SELECT COUNT(DISTINCT email) FROM users;

If the distinct count is close to the total row count, the column has high cardinality. If the number is much smaller, cardinality is low.

High cardinality vs. low cardinality

High cardinality columns contain mostly unique values. Common examples include user_id or email. These columns are great candidates for indexes because filtering on them usually narrows the result set quickly.

Low cardinality columns contain only a small set of repeating values. Examples include gender, country, or status. Indexing these columns on their own often provides little benefit because each value still matches a large number of rows.

Medium cardinality falls somewhere in between. Columns like city or department usually have more variety than status fields but still repeat across many rows. These columns can be useful in composite indexes, especially when combined with a higher cardinality column that further narrows the search.

Understanding where a column sits on this spectrum helps you make smarter indexing choices and avoid performance surprises as your data grows.

| Cardinality level | Example columns | Description |

| High | user_id, email | Mostly unique values per row |

| Medium | city, department | Some repetition across rows |

| Low | gender, status, country | Many repeated values across rows |

Relationship cardinality in data modeling

While column cardinality looks at values inside a table, relationship cardinality focuses on how tables connect to each other. This concept is central to data modeling and becomes especially important as your database grows in size and complexity.

In ER diagrams, this is often expressed using notations like 1:1, 1:N, or M:N.

What is relationship cardinality?

Relationship cardinality describes how many records in one table can be associated with records in another table. It helps you understand the nature of the connection between entities and guides how you structure tables and foreign keys.

You will often see relationship cardinality represented in entity relationship diagrams. These diagrams make it easier to visualize how data flows between tables and to spot design issues early.

Types of relationship cardinality

Relationship cardinality is typically categorized into three main types:

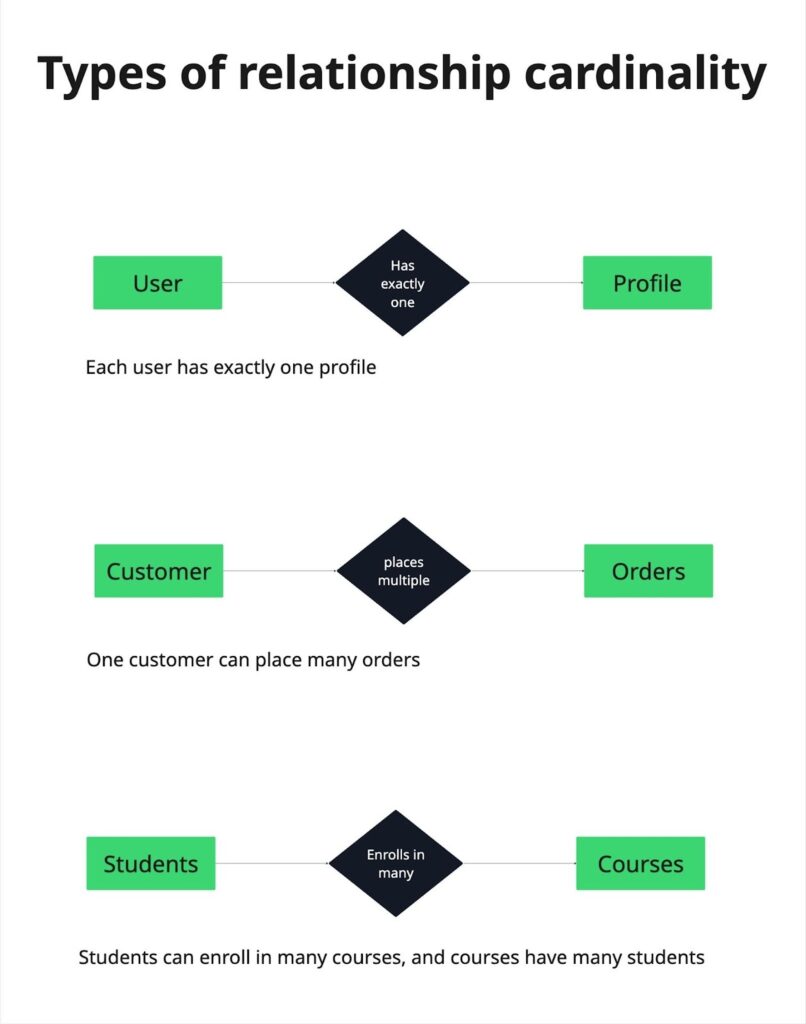

One-to-one (1:1)

In a one-to-one relationship, each record in one table is linked to exactly one record in another table. A common example is a user and a profile. Each user has one profile, and each profile belongs to one user. This setup is useful when you want to separate optional or sensitive data from the main table.

One-to-many (1:N)

In a one-to-many relationship, one record in the first table can be associated with many records in the second table. A classic example is a customer and their orders. One customer can place many orders, but each order belongs to a single customer. This is one of the most common relationships in database design.

Many-to-many (N:N)

In a many-to-many relationship, records in both tables can be linked to multiple records in the other table. Students and courses are a good example. A student can enroll in many courses, and a course can have many students. Databases usually handle this by introducing a junction table that stores the relationships explicitly.

Correct relationship cardinality prevents duplication, enforces foreign key constraints, and simplifies joins.

Minimum and maximum cardinality

Cardinality does not only describe the type of relationship between tables. It also defines how many related records are allowed or required. These rules are known as minimum and maximum cardinality constraints.

In ER diagrams, they are often written as (0..1), (1..1), or (1..N).

What does minimum and maximum cardinality mean?

Minimum cardinality defines the smallest number of related records that must exist and maximum cardinality defines the largest number allowed.

Together, they define the boundaries of a relationship and enforce business rules at the schema level.

For example, you might require that every order belongs to a user. In that case, the minimum cardinality on the order side is one. At the same time, an order can belong to only one user, which sets the maximum cardinality to one.

Optional vs. mandatory relationships

An optional relationship means the minimum cardinality is zero. A user may exist without placing any orders. A mandatory relationship means the minimum cardinality is one or more. For example, every order must be linked to a user.

Clear minimum and maximum constraints prevent invalid records and make relationship rules explicit.

Cardinality vs. selectivity

Cardinality and selectivity are closely related, but they are not the same thing. Mixing them up can lead to poor indexing decisions and unexpected query performance issues.

Understanding the difference

Cardinality is about how many distinct values exist in a column. Selectivity is about how effectively a specific value or condition filters rows in a query. In simple terms, selectivity answers the question, how much data does this filter remove?

To illustrate, let’s say a column with one million unique values has high cardinality. If you filter by a single value in that column, the database likely returns very few rows. That makes the condition highly selective.

When high cardinality does not mean high selectivity

High cardinality often leads to high selectivity, but this is not always true.

Consider a timestamp column where every row has a unique value. The column has high cardinality, but if most queries filter by a wide time range, the filter may still return a large portion of the table. In that case, selectivity is low even though cardinality is high.

The opposite can also happen. A low cardinality column like status might have only a few possible values, but if one value is rare, filtering on it can be very selective.

Why does this matter for index design?

Databases rely on selectivity when deciding whether to use an index. An index is most helpful when it significantly reduces the number of rows that need to be scanned.

Looking only at cardinality without considering how queries actually filter data can result in indexes that add overhead without improving performance.

When you design indexes, think about both concepts together. Cardinality tells you what is possible. Selectivity tells you what actually happens in real queries.

Query optimizers care more about selectivity than raw cardinality because selectivity determines how many rows must actually be processed.

| Cardinality | Selectivity | |

| Definition | Number of distinct values in a column | How well a filter reduces rows in a query |

| Examples | user_id has 1 million unique values → high cardinality | Filtering status = ‘active’ may return 10% of rows → high selectivity |

| Impact on queries | Guides indexing and join strategies | Determines how efficiently the database scans or filters rows |

Why cardinality matters for query performance

Cardinality directly affects how a database executes queries. Modern database engines rely on a query optimizer to choose the most efficient execution plan, and cardinality estimates are one of its primary inputs.

How query optimizers use cardinality?

The optimizer uses cardinality estimates to:

- Choose whether to use an index

- Decide the order in which tables are joined

- Estimate how many rows each step of a query will produce

When these estimates are accurate, the database selects an efficient execution plan. When they are wrong, performance can degrade quickly.

For example, imagine joining a users table (1,000,000 rows) with an orders table (50,000,000 rows) while filtering by a highly selective email column.

If the optimizer underestimates how selective that filter is, it may scan the large orders table first instead of filtering users early. That decision can multiply the amount of work required.

Why do wrong estimates cause slow queries?

Query performance often depends on the size of intermediate result sets.

Small result sets are inexpensive to process. They fit in memory and require fewer comparisons and disk reads. Large result sets are expensive. They increase I/O, consume memory, and slow down joins and sorting operations.

If the database underestimates cardinality, it may choose an execution plan optimized for small datasets that performs poorly at scale. Overestimates can also cause problems, leading the optimizer to avoid useful indexes.

Understanding cardinality helps you diagnose slow queries more effectively. It explains why a plan was chosen and what adjustments, such as updated statistics or better indexing, might improve performance.

What is cardinality estimation?

When you run a query, the database does not know the exact result size in advance. Instead, it makes an educated guess. This process is called cardinality estimation, and it has a huge impact on query performance.

How databases estimate cardinality

Databases estimate how many rows a query will return by relying on internal statistics. These statistics often include row counts, value distributions, and histograms that describe how data is spread within a column.

Using this information, the query optimizer predicts how selective a filter will be and how large each step of the query might grow.

PostgreSQL, MySQL, and SQL Server all depend heavily on this estimation process. While implementations differ, the goal is the same: select the most efficient execution plan before execution begins.

Where does estimation break down?

Problems occur when the assumptions behind cardinality estimates don’t match the actual data.

- Skewed data can create misleading estimates. For example, if most rows share the same value while a few rows have rare values, simple averages may not reflect the true distribution.

- Correlated columns present another challenge.Most query optimizers assume column independence unless extended statistics are defined. When two columns are correlated, like country and city, multiplying their selectivities can lead to serious under- or overestimation.

- Outdated statistics can also affect estimation. As data evolves over time, old statistics may no longer represent the current distribution, making predictions less reliable.

Why do inaccurate estimates matter?

When a database misestimates cardinality, it can choose a less efficient execution plan.

For example, it might use a nested loop join when a hash join would run faster, or overlook an index that could significantly reduce I/O.

As queries become more complex, these inefficiencies add up.

Knowing how cardinality estimation works helps you diagnose slow queries more effectively. It also explains why updating statistics and designing schemas with realistic data patterns in mind can make such a big difference in performance.

How to measure or inspect cardinality in SQL

You do not have to guess cardinality. Most databases give you simple ways to inspect it and see how the optimizer understands your data. A few basic SQL tools can already tell you a lot.

Count distinct values

The most direct way to measure column cardinality is to count how many unique values exist in a column. You can do this with a query like:

COUNT(DISTINCT column_name)

Comparing this number to the total row count gives you a clear picture of whether a column has high, medium, or low cardinality. This approach is straightforward and works well when you want an exact answer, although it can be expensive on very large tables.

Use statistics and analyze commands

Databases also maintain internal statistics that power cardinality estimation. Commands like ANALYZE update these statistics based on the current data. Running them regularly helps the optimizer make better decisions, especially after large data changes.

You usually do not query these statistics directly. Instead, you observe their effect through query plans and performance. Keeping statistics fresh is one of the easiest ways to avoid bad estimates.

Inspect cardinality with EXPLAIN

The EXPLAIN command shows how the database plans to execute a query. One of the most important parts of this output is the estimated number of rows at each step. These numbers represent the database’s cardinality estimates.

By comparing estimated row counts with actual results, you can spot where the optimizer is making wrong assumptions. Large gaps between estimated and actual rows are often a sign of skewed data, missing statistics, or poor index choices.

Together, these techniques give you visibility into how your database sees its own data. That insight makes it much easier to tune queries and fix performance problems before they affect users.

Cardinality and indexing strategy

Cardinality directly influences how effective an index will be. Knowing which columns have high, medium, or low cardinality can help you design indexes that actually improve query performance.

High vs. low cardinality columns

High cardinality columns are usually the best candidates for indexing. These columns contain mostly unique values, so filtering on them quickly narrows down the result set. For example, an index on an email or user_id column can dramatically speed up lookups.

Low cardinality columns, like status or boolean flags, often do not benefit from standalone indexes. Since each value appears in many rows, the database still has to scan a large portion of the table. Indexes on these columns can even add unnecessary overhead unless they are part of a composite index.

Composite indexes and cardinality order

Composite indexes combine multiple columns into a single index. In these cases, the order of columns matters.

Placing the higher cardinality column first makes the index more selective, helping the database eliminate rows earlier in the query. Low cardinality columns can follow if they further narrow down results.

For example, an index on (user_id, status) works well because user_id has high cardinality, while status helps filter results within each user. In contrast, an index on (status, user_id) is less efficient because the optimizer still has to scan many rows for each status value.

By aligning your indexing strategy with cardinality, you can reduce query execution time, lower I/O, and make your database more responsive. This is especially important in systems that handle frequent queries or large data volumes.

Common mistakes with cardinality

Even experienced developers and DBAs can trip up when it comes to cardinality. Understanding the pitfalls helps you avoid slow queries and inefficient designs.

Confusing relationship cardinality with column cardinality

One of the most frequent mistakes is mixing up the two types of cardinality. Column cardinality is about unique values in a single column, while relationship cardinality describes how tables connect.

Treating them interchangeably can lead to incorrect assumptions about indexes, joins, or foreign key constraints.

Indexing low-cardinality columns blindly

Not every column needs an index. Creating indexes on low-cardinality columns, like boolean flags or a small set of status values, rarely improves performance.

In some cases, it adds unnecessary overhead for writes and storage. Always consider whether the index will actually filter rows efficiently.

Ignoring skewed data

Cardinality metrics often assume a uniform distribution of values. In reality, data is rarely evenly spread. Skewed data, where a few values dominate a column, can make an index or query plan less effective than expected. Checking distributions helps prevent surprises.

Assuming optimizer estimates are always correct

Modern query optimizers are smart, but they rely on statistics and heuristics. Blindly trusting them can lead to poor execution plans when statistics are outdated, data is correlated, or distributions are unusual. Regularly updating statistics and validating estimates against actual query results keeps your database performing well.

Practical use cases

In real-world systems, cardinality directly affects performance, storage, and query efficiency. Here are some examples where thinking about cardinality makes a big difference:

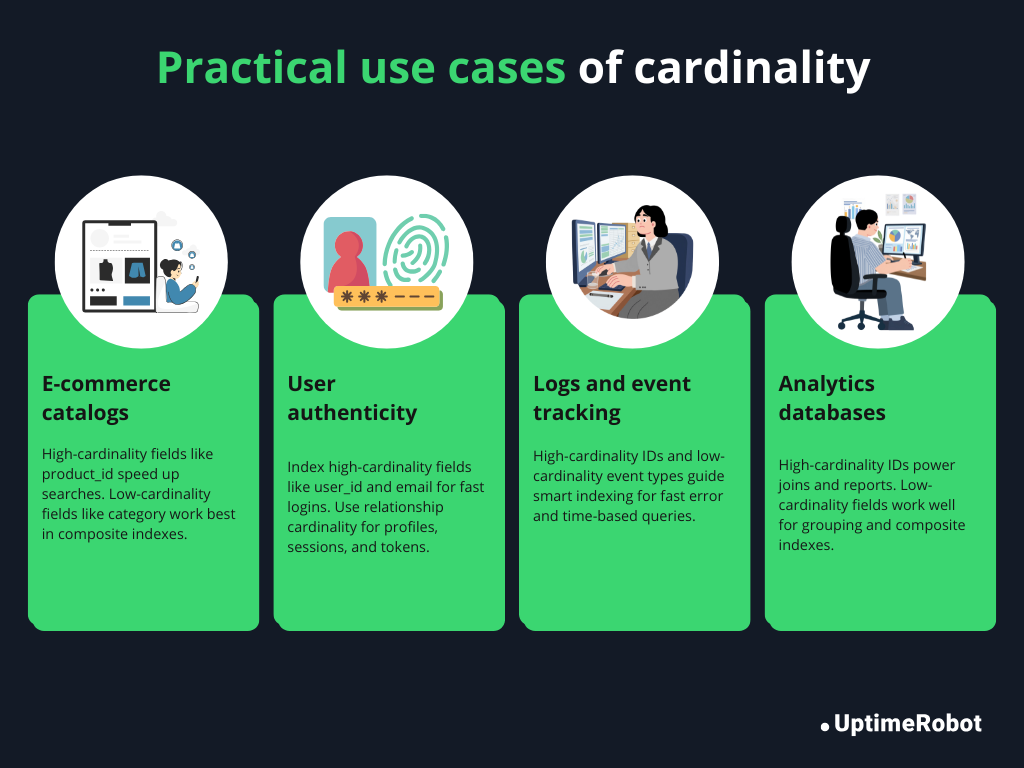

E-commerce product catalog

In a product catalog, columns like product_id or SKU have high cardinality, while category or availability_status often have low cardinality. Indexing high-cardinality columns speeds up product searches and lookups, while knowing the low-cardinality columns helps avoid unnecessary indexes. Composite indexes, like (category, price), can make filtering and sorting much faster.

User authentication tables

Tables that store user credentials typically include high-cardinality columns such as user_id and email. Proper indexing here is crucial for login operations and password resets.

Relationship cardinality also matters: each user has one profile (one-to-one) but can have many sessions or API tokens (one-to-many). This helps define foreign keys and prevent orphaned records.

Log and event tracking systems

Logs often generate huge volumes of data. Columns like event_id are high-cardinality, while event_type or status might be low. Knowing column cardinality helps you choose which fields to index, so queries, like finding all errors from the last 24 hours, run quickly without scanning the entire table.

Analytics databases

In analytics, queries often involve aggregating and joining large datasets. Columns with high cardinality, like customer_id or transaction_id, determine which indexes will speed up reporting.

Low-cardinality columns, like region or subscription_type, may be useful in composite indexes or as group-by dimensions. Recognizing cardinality patterns ensures dashboards load quickly and aggregations remain performant.

Conclusion

Cardinality is a fundamental concept in databases that affects almost every part of design and performance. It determines how tables relate to each other, guides which columns to index, and helps the database execute queries efficiently.

By understanding both column and relationship cardinality, you can design schemas that are organized, scalable, and optimized for real-world use. You’ll avoid common pitfalls, like indexing low-cardinality columns unnecessarily or misjudging table relationships.

Keeping cardinality in mind helps your database handle large datasets, run queries faster, and stay maintainable. In short, mastering cardinality is a practical skill that makes your systems more efficient, reliable, and future-proof.

FAQ's

-

High cardinality refers to a column that contains mostly unique values. Examples include user_id or email. Columns like these are often good candidates for indexing because filtering on them quickly reduces the number of rows returned.

-

Cardinality influences how the database chooses indexes, join orders, and query execution plans. High cardinality columns can make queries faster when indexed, while incorrect assumptions about cardinality can lead to slow queries and inefficient operations.

-

Cardinality measures the number of distinct values in a column. Selectivity measures how effectively a filter reduces the number of rows returned by a query. High cardinality often leads to high selectivity, but not always, depending on data distribution and query patterns.

-

Databases use statistics, histograms, and other metadata to estimate how many rows a query will return. Systems like PostgreSQL, MySQL, and SQL Server rely on these estimates to choose indexes and join strategies. Inaccurate estimates can result in poor execution plans.

-

Not usually. Low cardinality columns, such as status or boolean flags, often do not benefit from standalone indexes. They may be useful in composite indexes when combined with higher cardinality columns.

-

The concept is similar: it describes uniqueness or relationship patterns. However, NoSQL databases may handle relationships and indexing differently, so the practical implications of cardinality can vary depending on the database model.