TL;DR (QUICK ANSWER)

Incident communication is a structured system, not a one-time message. It defines who communicates, through which channels, using which templates, and how often updates are shared. Strong incident communication acknowledges issues early, explains customer impact clearly, and sets expectations for the next update. Different audiences need different levels of detail, engineers need technical context, while customers need simple, trustworthy updates. Success is measured with KPIs like time to acknowledge, time to first customer update, update consistency, and customer sentiment.

Most incident communication fails for a simple reason. Teams treat it as a one-off message instead of a system.

When something breaks, technical response takes over. Communication becomes reactive, inconsistent, or delayed. Updates get written on the fly, different teams share different versions of the truth, and customers are left guessing what is happening. In many cases, the confusion causes more damage than the incident itself.

Incident communication is as important as incident response. It shapes customer trust, internal alignment, regulatory exposure, and how quickly teams recover. Clear communication reduces support load, speeds up decision-making, and helps keep a small outage from turning into a reputation problem.

This article breaks down incident communication end to end, from planning and roles to templates, timing, and the metrics that show whether your process is working.

Key takeaways

- Incident communication is a system of roles, channels, templates, cadence, and a clear source of truth.

- Acknowledge early, explain impact plainly, and set update expectations.

- Engineers, execs, support, customers, and partners do not need the same detail.

- Severity-based templates reduce mistakes

- A few KPIs reveal gaps fast: time to acknowledge, time to first customer update, update consistency, and sentiment signals.

What is incident communication?

Incident communication is the structured way teams share information when a service disruption, degradation, or outage occurs.

It sits alongside incident response, not after it. While incident response focuses on fixing the technical problem, incident communication focuses on keeping people aligned while that work happens. The goal is clarity, not constant updates.

Incident communication answers four questions:

- What is happening right now?

- Who is affected and how?

- What is being done to fix it?

- When will the next update arrive?

This applies to both internal and external audiences. Engineers need context to act quickly, support teams need accurate language to respond to customers, executives need a clear picture of risk and impact, and customers need timely, plain-language updates they can trust.

Incident communication isn’t a single message. It’s a system made up of roles, workflows, channels, templates, and timing rules. When that system is missing, communication becomes improvised. Messages drift, updates lag, and trust erodes.

When the system is in place, teams communicate early, consistently, and with confidence, even when the root cause is still unclear.

How it fits into incident management

Incident management usually includes detection, triage, mitigation, resolution, and review. Communication runs through all of those stages.

- During detection: acknowledge that something is wrong.

- During response: share impact, progress, and expectations.

- During resolution: confirm recovery and stability.

- After resolution: explain what happened and what changed.

Communication is not a separate phase. It is continuous, and it needs ownership just like any other part of incident management.

Why communication is a system, not a message

Single updates fail because of things like incidents evolving, changes in information, or new stakeholders getting involved.

A system prevents common failure points:

- Updates coming too late or not at all.

- Different teams sharing conflicting information.

- Overly technical messages sent to non-technical audiences.

- Promises made without confidence in timelines.

Well-designed incident communication systems rely on predefined severity levels, clear ownership, agreed channels, and reusable templates. That structure cuts cognitive burden during high-pressure moments and keeps communication steady when teams are focused on fixing the issue.

Incident communication vs. crisis communication

Incident communication and crisis communication are often used interchangeably, but they are not the same thing. Confusing the two leads to overreaction in minor situations and underreaction when the risk is real.

| Aspect | Incident communication | Crisis communication |

| Scope | Operational disruptions affecting availability or performance | High-impact situations threatening business continuity or reputation |

| Duration | Usually time-bound and resolved within normal response windows | Often prolonged and unpredictable |

| Impact level | Limited or localized user and service impact | Broad impact across customers, partners, or the public |

| Ownership | Engineering, SRE, or operations teams | Executive leadership with legal and communications involvement |

| Primary risk | Service reliability and operational disruption | Legal exposure, reputational damage, and long-term trust loss |

| Typical examples | API latency, partial outages, failed deployments | Data breaches, extended multi-service outages, public incidents |

Now, let’s get into more detail.

Scope and scale

Incidents are usually localized to a service, feature, region, or subset of users. Crises tend to affect multiple systems, large portions of the user base, or the entire organization.

Audience and exposure

Incident communication targets internal teams and affected customers. Crisis communication often reaches a much broader audience, including all customers, partners, regulators, and sometimes the public or media.

Risk profile

Incidents carry operational risk. Crises carry legal, financial, and reputational risk. This changes what can be said, how quickly messages must be reviewed, and who approves them.

Ownership

Incident communication is typically led by engineering, SRE, or an incident commander. Crisis communication is owned at the executive level and often involves legal and public relations teams.

When an incident becomes a crisis

An incident becomes a crisis when one or more of the following is true:

- Customer data or security is involved.

- The outage is prolonged with no clear resolution path.

- A large percentage of customers are affected.

- Regulatory or contractual obligations may be breached.

- Public attention or media scrutiny increases.

An incident does not always become a crisis at once. Issues can escalate gradually as impact spreads, timelines stretch, or communication falters.

Overreacting to routine incidents drains attention and credibility. Underreacting to a real crisis does the opposite. It slows response, fragments messaging, and erodes trust when it matters most.

Clear definitions and escalation thresholds help teams recognize when the situation has changed and respond accordingly, with the right tone, ownership, and stakeholders involved.

Why incident communication matters

When systems fail, communication often has as much impact as the technical fix. Poor communication amplifies confusion, slows recovery, and damages trust long after the incident is resolved.

Incident communication matters because it directly affects:

- Trust and transparency: early acknowledgement reduces uncertainty and speculation, even before full details are known.

- Customer retention during outages: customers are more likely to tolerate downtime when they feel informed rather than ignored.

- Internal alignment and speed: a shared source of truth prevents duplicated work, outdated responses, and slow decision-making.

- Support load and escalation: clear updates reduce inbound tickets and reactive firefighting.

- Regulatory and contractual risk: documented, timely communication supports audits, compliance reviews, and customer obligations.

Poor communication often causes more damage than the incident itself. Systems recover. Trust does not always do the same.

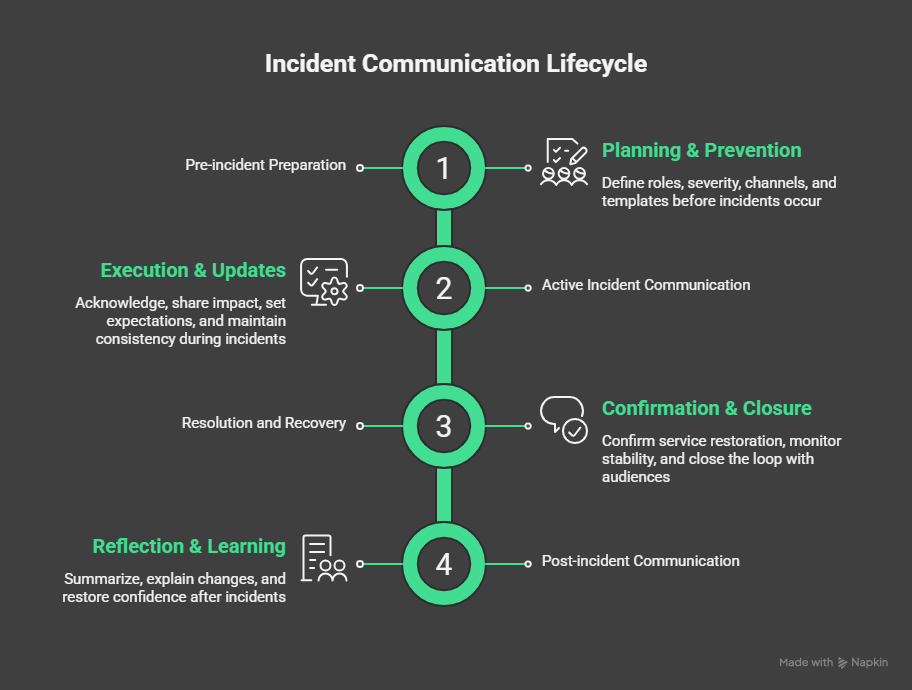

The incident communication lifecycle

Incident communication works best when it follows a clear lifecycle. Each stage has a different goal, a different audience focus, and different risks if handled poorly.

Treating communication as a continuous process helps teams stay aligned while incidents evolve.

Pre-incident preparation

This stage happens before anything breaks. It is where most communication failures are either prevented or guaranteed.

Preparation includes:

- Defining ownership and decision rights.

- Setting severity levels and escalation rules.

- Choosing channels and a single source of truth.

- Writing templates that can be reused under pressure.

Teams that skip this stage rely on improvisation during incidents. That almost always leads to delays, inconsistent messages, and unnecessary stress.

Active incident communication

Once an incident is detected and confirmed, communication shifts into execution mode.

The priorities here are:

- Acknowledge the issue quickly.

- Share confirmed impact, not speculation.

- Set expectations for update timing.

- Keep messages consistent across channels.

At this stage, clarity matters more than completeness. It is better to say “we’re investigating” than to wait for a perfect explanation.

Resolution and recovery

When the technical issue is fixed, communication isn’t finished.

Teams need to:

- Confirm that service has been restored.

- Share when monitoring shows stability.

- Close the loop with the same audiences that received updates during the incident.

Skipping this step leaves users uncertain whether the problem is truly resolved or just temporarily quiet.

Post-incident communication

After resolution, communication becomes reflective.

This stage focuses on:

- Summarizing what happened in clear language.

- Explaining what changed to prevent recurrence.

- Restoring confidence after visible or prolonged incidents.

Post-incident communication turns operational failures into learning moments. It also signals accountability and maturity to customers and stakeholders.

Each stage of the lifecycle builds on the previous one. Weak preparation makes active communication harder, while poor resolution messaging undermines trust. And skipping post-incident follow-up wastes the opportunity to improve.

Pre-incident communication planning

Incident communication rarely fails because teams do not care. It fails because decisions are made for the first time during an incident.

Pre-incident planning removes guesswork. It defines who communicates, how information flows, and what “good” looks like before pressure hits.

Defining ownership and roles

Every incident needs clear communication ownership. Without it, updates stall or multiple people share conflicting messages.

At a minimum, define:

- An incident commander who owns overall coordination.

- A communication owner responsible for internal and external updates.

- Technical leads who supply accurate status and impact details.

These roles can rotate and scale with severity. What matters is that ownership is explicit and known in advance.

Creating severity levels

Severity levels help teams decide how much communication is required and how fast it should happen.

A simple model works best:

- Low severity: limited impact, internal updates only.

- Medium severity: partial user impact, regular updates to affected stakeholders.

- High severity: major customer impact, frequent updates and leadership visibility.

Severity should drive cadence, channels, and tone. It should never be debated during an incident.

Tip: Severity levels can be subjective, unless you define them ahead of time. Read our guide to severity levels to learn more and create a unified system.

Building communication playbooks

A communication playbook documents how incidents are communicated, step by step.

Strong playbooks include:

- When to acknowledge issues publicly.

- Which channels to use by severity.

- Update frequency expectations.

- Escalation triggers.

- Example messages for common scenarios.

With a playbook in place, teams are not deciding how to communicate while systems are already failing. The decisions are made ahead of time.

Channel selection by audience

Not every channel fits every audience.

Before incidents happen, decide:

- Where engineers coordinate.

- Where support teams get official updates.

- Where customers check status.

- Which channel is the single source of truth.

Clear channel rules prevent over-communication and avoid situations where customers see updates before internal teams do.

Incident simulations and drills

Tabletop exercises and simulations expose gaps quickly.

Good drills test:

- Whether alerts reach the right people.

- How fast the first acknowledgement goes out.

- Whether updates stay consistent across channels.

- Whether ownership is clear when pressure increases.

Fixing these gaps in practice is far cheaper than fixing them during a real outage.

Pre-incident communication planning isn’t useless overhead. It’s what allows teams to communicate clearly when everything else is unstable.

Stakeholder-based communication strategy

Incident communication fails when everyone receives the same message. Different stakeholders operate on different timelines, care about different risks, and need different levels of detail.

Here’s a general breakdown of who needs to know what:

Internal engineering teams

Engineering communication should prioritize signal over polish. Speed and accuracy matter more than wording.

| Aspect | Guidance |

| What they need to know | What’s failing, how it’s failing, scope of impact, and how the incident is evolving |

| Update frequency | High during active response, often continuous during mitigation |

| Tone and level of detail | Direct, technical, and precise. Logs, metrics, timelines, and hypotheses are appropriate |

| Primary objective | Enable fast diagnosis and resolution |

Executive leadership

Executives should never need to reconstruct the situation from scattered updates.

| Aspect | Guidance |

| What they need to know | Business impact, customer impact, duration, risk, and exposure |

| Update frequency | Triggered by severity changes, impact shifts, or escalation thresholds |

| Tone and level of detail | Concise and calm. Focus on outcomes, not implementation details |

| Primary objective | Support decision-making and risk management |

Customer support and sales

Support teams act as an extension of incident communication. Misalignment is immediately visible to customers.

| Aspect | Guidance |

| What they need to know | Clear, reusable language explaining impact, limitations, and expected updates |

| Update frequency | Regular and predictable. Always ahead of or aligned with public updates |

| Tone and level of detail | Plain language, no internal jargon, clear guidance on what to say and not say |

| Primary objective | Enable consistent, confident customer communication |

Customers and users

Customers don’t need full technical context. They need enough information to feel informed and confident the situation is under control.

| Aspect | Guidance |

| What they need to know | Whether they are affected, how it impacts them, and when the next update will arrive |

| Update frequency | Early acknowledgement followed by steady, predictable updates |

| Tone and level of detail | Clear, honest, and calm. Avoid internal system names and speculative timelines |

| Primary objective | Maintain trust and ease uncertainty |

Partners and regulators

These audiences often review communication after the incident. Accuracy and traceability matter more than speed.

| Aspect | Guidance |

| What they need to know | Contractual impact, compliance exposure, timelines, and documented facts |

| Update frequency | Driven by regulatory or contractual requirements |

| Tone and level of detail | Formal, factual, and documented |

| Primary objective | Meet legal, regulatory, and contractual obligations |

Communication channels and timing

Choosing the right channel is as important as writing the right message. A clear channel strategy helps teams reach the right audience, avoid noise, and prevent contradictory updates during incidents.

| Channel | Best used when | Why it works | Watch outs |

| Status pages | Customer-facing incidents or widespread impact | Single source of truth, easy to find, supports frequent timestamped updates | Not suitable for internal coordination |

| Email updates | Prolonged incidents, targeted customer impact, user action required | Direct delivery, good for detailed explanations | Too slow for first acknowledgement, hard to retract |

| In-app notifications | Users are active and a specific feature is affected | Contextual, immediate reassurance | Disruptive if overused, must stay brief |

| Internal chat tools (Slack, Teams) | Active incident response and coordination | Real-time updates, fast alignment across teams | Needs dedicated channels to avoid noise |

| Social media | Large-scale incidents with public visibility | Controls narrative and reduces misinformation | Should stay high-level and point to status page |

Status pages should anchor external communication. Other channels should reinforce them, not compete with them.

Timing and cadence

Timing matters more than precision. Consistent communication builds confidence even when progress is slow.

Best practice:

- Acknowledge the incident as soon as it is confirmed.

- Set expectations for when the next update will arrive.

- Stick to a predictable cadence, even if there is no new information.

A short update that says nothing has changed is better than silence. Silence creates uncertainty.

Avoiding contradictory messaging

Contradictions usually happen when multiple channels are updated independently.

To prevent this:

- Designate a single source of truth.

- Assign one owner for external messaging.

- Link all other channels back to the primary update location.

If stakeholders need to compare Slack messages, emails, and social posts to understand what is happening, communication has already failed.

Incident communication templates by severity

Templates remove friction when time and attention are limited. They help teams communicate quickly without improvising tone, structure, or promises under pressure.

These examples are intentionally simple and designed to be reused, adjusted slightly, and sent with confidence.

Low severity incident template

Use this for minor issues with limited impact or internal-only relevance.

When to use:

- No customer-facing impact, or impact is minimal.

- Core functionality is unaffected.

- No immediate action required from users.

Subject: Minor issue identified: [Service or feature name]

We’ve identified a minor issue affecting [brief description].

This issue does not impact core functionality, and most users are not affected. The team is investigating and will monitor the situation.

We’ll share an update if the status changes.

Tone guidance: Calm and factual. No urgency language. Don’t over-explain.

Medium severity incident template

Use this for partial outages, degraded performance, or issues affecting a subset of users.

When to use:

- Noticeable impact to some users.

- Performance degradation or feature instability.

- Active investigation and mitigation underway.

Subject: Service degradation affecting [service or feature]

We’re currently investigating an issue affecting [service or feature].

Some users may experience [specific impact]. Our engineering team is working to identify the cause and restore normal operation.

Next update: [time or time range].

Tone guidance: Clear and steady. Acknowledge impact without speculation. Always set a next update expectation.

High severity or customer-impacting incident template

Use this for major outages, widespread impact, or incidents requiring frequent updates and leadership visibility.

When to use:

- Core service is unavailable or severely degraded.

- Large percentage of users affected.

- High support volume or business impact.

Subject: Major service disruption: [service name]

We’re currently experiencing a major issue affecting [service or feature].

Users may be unable to [key functionality]. Our incident response team is actively working on mitigation and recovery.

Next update: [specific time or interval].

We understand the impact this may have and will continue to share updates as we make progress.

Tone guidance: Direct and accountable. Avoid defensive language. Don’t promise resolution timelines unless you’re confident.

Templates also prevent two common mistakes:

- Saying too little early.

- Saying too much or too confidently too soon.

They create a baseline that can be improved over time as teams review what worked and what did not.

Metrics and KPIs for incident communication

You can’t improve incident communication without measuring it. The metrics below focus on communication quality and reliability, not just technical recovery.

| Metric | What it measures | Why it matters | How to track it |

| MTTA (Mean Time to Acknowledge) | Time from incident detection to first acknowledgement | Early acknowledgement reduces uncertainty and signals control. Long MTTA often means unclear ownership or missed alerts | Compare detection timestamp with first internal or public acknowledgement |

| MTTR (Mean Time to Resolution) | Time from detection to full resolution | Longer incidents increase the risk of communication breakdowns and missed updates | Use incident timelines from monitoring and incident management tools |

| Time to first customer update | Time from detection to first customer-facing message | Customers expect acknowledgement before resolution, not after | Measure time to first status page update, email, or in-app message |

| Update frequency consistency | Whether updates follow the promised cadence | Irregular updates erode trust faster than slow progress | Compare promised update intervals with actual update timestamps |

| Customer sentiment signals | Qualitative feedback during and after incidents | Reveals clarity gaps that timestamps cannot show | Review support volume, ticket tone, survey responses, and feedback |

Metrics only matter if they drive change.

After incidents:

- Review communication KPIs alongside technical metrics.

- Identify where acknowledgement, cadence, or clarity broke down.

- Update templates, playbooks, tooling, or ownership rules accordingly.

Strong teams treat communication metrics the same way they treat reliability metrics. They review them regularly and improve the system, not just individual messages.

Common incident communication mistakes to avoid

Most incident communication failures follow predictable patterns. They are rarely caused by bad intent. They happen when pressure exposes gaps in planning, ownership, or discipline.

Avoiding these mistakes has an outsized impact on trust, recovery speed, and credibility.

| Mistake | Why it happens | Why it causes damage | What to do instead |

| Saying nothing for too long | Teams wait for certainty before speaking | Silence creates anxiety, speculation, and loss of confidence | Acknowledge early, even if details are limited |

| Over-promising resolution timelines | Desire to reassure users quickly | Missed estimates erode trust faster than uncertainty | Commit to update cadence, not fix times |

| Sharing too much technical detail | Engineers default to internal language | External audiences lose clarity and confidence | Focus on impact and next steps, not internals |

| Inconsistent updates across channels | No single source of truth or owner | Conflicting messages damage credibility | Designate one owner and one primary update location |

| Ignoring post-incident follow-up | Focus shifts back to delivery too quickly | Users feel abandoned, teams miss learning | Share a resolution summary and clear next steps |

A short resolution summary and visible follow-up actions signal accountability and operational maturity.

Post-incident communication and learning

What happens after an incident often determines whether trust is restored or quietly eroded.

Post-incident communication serves two purposes: learning internally and rebuilding confidence externally.

Internal postmortems and summaries

Internally, teams need a clear, shared understanding of what happened.

A strong post-incident review focuses on:

- A factual timeline of detection, response, communication, and resolution.

- Where communication lagged, broke down, or caused confusion.

- What signals were missed or misinterpreted.

- Which decisions helped reduce impact.

The goal is improvement, not blame. Blameless postmortems encourage honesty and lead to better systems and clearer communication processes.

Every review should produce concrete follow-ups, such as updated templates, clearer ownership, improved alerting, or revised severity definitions.

Tip: Postmortems are where incident communication gets better. Our postmortem guide shows how to document incidents clearly and turn them into real process improvements.

Communicating what changed

If customers noticed the incident, they deserve to know what was done to prevent it from happening again.

Post-incident communication should clearly explain:

- What caused the issue at a high level.

- What was done to fix it.

- What safeguards or changes were put in place.

You don’t need to expose sensitive implementation details, you just need clarity and accountability. Vague language creates doubt, but specific actions build confidence.

Rebuilding trust after major incidents

For high-impact incidents, a simple “resolved” message isn’t enough. Customers want reassurance that the same failure won’t repeat. Clear follow-up communication helps reset expectations and shows that lessons were taken seriously.

Strong teams treat post-incident updates as part of customer experience, not damage control.

Feeding lessons back into playbooks

Learning only matters if it changes future behaviour.

After each incident:

- Update communication playbooks based on what failed or slowed teams down.

- Refine templates to reflect real-world usage.

- Adjust escalation thresholds or cadence expectations.

- Revisit roles if ownership was unclear.

Over time, these small improvements compound. Communication becomes faster, calmer, and more consistent under pressure.

Tools and automation for incident communication

Good incident communication depends on systems, not heroics. The right tools reduce manual work, speed up acknowledgements, and keep messages consistent when teams are under pressure.

This section focuses on capabilities, not vendors. Tools should support your communication strategy, not define it.

Alerting and monitoring tools

Incident communication starts with detection. If alerts are slow, noisy, or misrouted, communication breaks before it begins.

Strong alerting tools:

- Detect failures quickly and reliably.

- Route alerts to the right on-call responders.

- Include enough context to support fast acknowledgement.

Monitoring platforms like UptimeRobot can trigger alerts across multiple channels the moment an incident is detected.

Status pages

Status pages are the most effective external communication tool during incidents.

They work because they:

- Act as a single source of truth.

- Cut inbound support requests.

- Allow frequent, low-friction updates.

A well-maintained status page makes it clear where customers should look for updates. Other channels should point back to it rather than competing with it.

Automation and templates

Automation removes repetition and reduces error risk.

Useful automation includes:

- Pre-filled incident updates based on severity.

- Automatic timestamps and incident IDs.

- Scheduled reminders to post updates at agreed intervals.

Templates combined with automation let teams communicate consistently, even during long or complex incidents.

Incident management platforms

Incident management tools help coordinate response and communication across teams.

They typically support:

- Incident ownership and escalation.

- Timelines and activity logs.

- Integration with monitoring and messaging tools.

- Data for post-incident reviews.

When integrated properly, these platforms create a clear record of what happened, when it was communicated, and to whom.

The role of AI

AI can support incident communication, but it shouldn’t replace human judgment.

Practical uses include:

- Summarizing incident timelines after resolution.

- Drafting first-pass updates that humans review.

- Highlighting inconsistencies across channels.

- Extracting communication metrics from incident logs.

AI works best as an assistant, not an authority. Final messages should always be reviewed by someone who understands context, risk, and audience.

Choosing the right stack

There is no single “correct” toolset.

The best stack is one that:

- Matches your incident communication workflow.

- Integrates cleanly with existing systems.

- Is simple enough to use under stress.

Tools should fade into the background during incidents. If teams are fighting the tooling, communication will suffer.

Conclusion

Incident communication is not a soft skill or a secondary concern. It is a core operational system that determines how effectively teams respond when things break.

Strong teams communicate early, clearly, and consistently because they plan for it. They define ownership, agree on severity levels, choose the right channels, and rely on templates instead of improvisation. During incidents, this structure reduces confusion and cognitive load. After incidents, it creates learning loops that improve future response.

Poor communication often causes more damage than the outage itself. Clear communication limits that damage, protects trust, and helps teams recover faster, both technically and reputationally.

When incident communication is treated with the same rigor as monitoring and response, incidents become manageable events instead of chaotic failures.

FAQ's

-

The goal is to keep stakeholders informed, aligned, and confident while an incident is being resolved. Good incident communication eases uncertainty, prevents speculation, and supports faster decision-making internally and externally.

-

Ownership should be explicit. In most organizations, an incident commander oversees the response, while a designated communication owner manages updates. The key is clarity. Communication should never be owned by everyone or no one.

-

Updates should follow a predictable cadence based on severity. High-impact incidents often require updates every 15 to 30 minutes. Lower-severity incidents may only need acknowledgement and change-based updates. Consistency matters more than frequency.

-

Avoid speculation, unverified root causes, and confident resolution timelines you can’t guarantee. Do not share sensitive security details or internal debates. Focus on confirmed impact, current status, and when the next update will arrive.

-

Good incident communication can be measured using metrics like time to acknowledge, time to first customer update, update consistency, and customer feedback. These signals reveal whether communication was timely, clear, and trustworthy during real incidents.